HISTORY | The fifth change

The number of substitutions in a game has been increased and Real Betis have been adapting to these modifications since 1969, when changes were introduced

By Manolo

Rodríguez

It has been announced that once LaLiga returns, each team will have the chance to make five substitutions in one match. An exceptional rule that is aimed to prevent the effects of the long break provoked by the pandemic and the high temperatures that are expected in the weeks when the competition is going to be played.

It is about protecting the footballers, which is basically protecting football itself. It seems like a good idea that has created no controversy whatsoever and that was approved by the International Board, a body in charge of defining and modifying football rules.

This increase in the number of substitutions in a game is a continuation to the path set in the 60s of the 20th Century. Until then, only replacing the goalkeeper, and only if he was injured, was allowed.

That was changed at the beginning of the 1969/1970 season, when the aforementioned International Board allowed the teams to make two changes in a game. A measure of great impact, as it meant a change in the style of playing that would be decisive in the future.

On one hand, it allowed to increase the number of players in a call-up and to have more players involved in the competition. One the other hand, it offered coaches to have a variety of tactics. They now could change their initial ideas by replacing a player.

However, that new rule was, at first, a shock in comparison with the past. The coaches, back then regarded as craftsmen, struggled to adapt to this new model in which not only strategy knowledge was valued, but also certain flexibility they were not used to.

In fact, Real Betis did not make two changes in a single game until Match 13 of said 1960/70 season. And this decision was made by the assistant manager, Antonio Barrios, who had taken the reins of the team three weeks before.

Because the head coach at the beginning of that year, Miguel González, had not used this possibility of substitutions much during the first 10 weeks. He clearly showed that changes were only necessary if a player was injured or, exceptionally, introducing more strikers when the game was missing goals.

That is certainly what happened the first time such event took place. It was a Betis-Sporting played in September of 1969. Midfielder Dioni was substituted off and striker Landa took his place.

The first time Real Betis made two changes in a single game was in a match played against Salamanca at home. A cold Sunday, 30th of November of 1969. Santi came on for Demetrio in the 50th minute and Mellado replaced Pepe González in the 75th. The Green and Whites won 1-0, thanks to goal scored directly from a corner kick by Rogelio Sosa when only four minutes were remaining.

Once that adaptation time was over, the two substitutions rule was normalized and became an element that was used to measure the quality of the game, the composition of the squads and the performance of the teams.

This measure survived for a quarter of a century until the 1994/95 season. Another step was taken forward then when a new rule was introduced: apart from the two changes, the goalkeeper could also be replaced. A case that Betis did not have the need to use, as the goalkeeper, Pedro Jaro, played all the minutes in LaLiga. And he did it so well that, as it is known, he was the Golden Glove of LaLiga, as he only conceded 25 goals in the entire season.

The Copa del Rey matches were played by the second keeper, Jose Luis Diezma, who also played the six games entirely. So Real Betis never found themselves in the situation of making the two field players changes plus the keeper.

The revolution of 95

That rule did not stand for long, though, because, at the beginning of the 1995/96 season, one of the biggest revolutions in Spanish football took place. Four major changes came that year.

First of all, the Spanish Federation approved, with the intention of promoting offensive football, a new points system. This way, the winner of a game would be awarded 3 points instead of 2, but maintaining one point in case of a draw and 0 for the loser.

This measure had been used in the English league since 1981 and was initially only followed in Israel (1982), Turkey (1987) and Norway (1998). Until 1994, when the FIFA decided to use this system first in the 1994 USA World Cup and then in the rest of competitions.

Apart from that, LaLiga decided to increase the number of foreign players that a club could have, up to five. The exception was that, during a game, only three of these foreigners could play at the same time.

A rule that almost caused Real Betis a problem in 1996 when Betis hosted Racing de Santander at Benito Villamarín. The team was playing with the three foreigners allowed by the rule (Vidakovic, Jarni and Kowalczyk) but the bench planned to then play Stosic (the fourth foreigner in the squad) to replace Sabas. That wasn't allowed and someone in the bench realized just in time. Then, Pier came on for Sabas and, a few minutes later, Stosic replaced Kowalczyk.

The third innovation of that summer of 95 was that the players started to use the same number for the whole season. Numbers 1 to 22 were for the pros and 23 on for the Academy players. Also, the same rule made compulsory to display the name of the player on the back of the shirt.

Let's take a look to the numbers Real Betis had that year:

1. Jaro

2. Jaime

3. Menéndez

4. Ureña

5. Josete

6. Merino

7. Alexis

8. Márquez

9. Stosic

10. Cañas

11. Alfonso

12. Sánchez Jara

13. Diezma

14. Vidakovic

15. Pier

16. Kowalczyk

17. Jarni

18. Arpón

19. Sabas

20. Olías

21. Roberto Ríos

22. José Mari

Since the first day

The fourth modification that the 1995/96 season brought was the possibility of making three changes during a game, without one of them having to be for the keeper. This decision was aimed to the high consumption football of the latest decades, with long and demanding competitions and teams in need of having large squads that allowed them to play several games in few days.

The new rule went into effect in the first match of that season and Betis, like everyone else, used them all. The Green and Whites started the season with a draw in Mérida (1-1). That day, Alfonso Pérez made his debut with the shirt of the Thirteen Stripes.

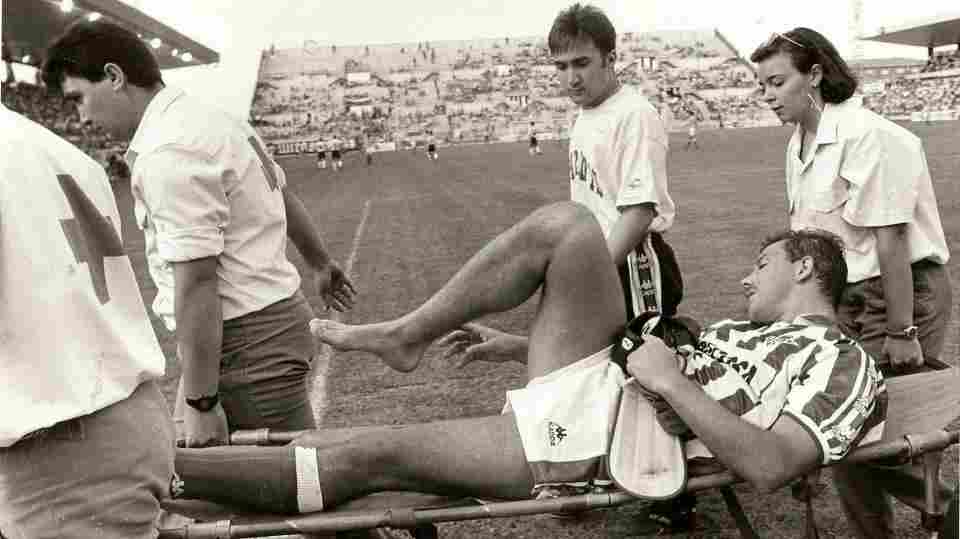

The first of the three changes that evening came, as it happened before, due to an injury. Polish striker Kowalczyk received a hard tackle that broke his fibula and forced him to leave the pitch in the 41st minute. Sabas took his place. The Polish was four months out.

The other two changes were made in the second half. Merino did not come back from the dressing room after half time and Jaime came on for him. In the 81st minute, José Mari replaced Cañas.

Since that day, the three changes became part of our football. So key that football reports in newspapers used to criticize coaches who did not use all of them. In general, at first, were used to replace injured players, adjust minor tactical aspects, bring off tired players and, in the last minutes, waste time.

They were usually made separately along the game and, for that reason, the fact that Real Betis manager, Lorenzo Serra, made the three changes at once drew a lot of attention. He actually did it twice, in two games played away. And it worked out fine both times.

But such drastic determinations have been the exception in these last two decades. It is so much so that this new rule of five changes establishes that they have to be made in different moments so the final stage of a game does not become a carousel of substitutions.

Another milestone in football history. And this time, Real Betis will be one of the two teams to use it. And in a derby, no less.